Demystifying the Pattern(s) of Change: A Common Archetype

We are all familiar with it because we have ridden its wave many times in our lives. Some of us have developed the wisdom to embrace it when it arises; others are still resisting it, stricken by anxiety and fear when sensing it’s coming. Most of us, not always happily, are accepting it as an avoidable element of life. Perhaps a few have learned to enjoy it. We hate to be forced into it and we have become skilled at finding ways to turn our back to it, often in denial. Yet, avoiding it only makes its process more difficult; it will return. When we must face it, we too often try to control it. Of course, you know what ‘beast’ I am speaking about. Ladies and gentlemen, let me introduce to you “CHANGE!”

Perhaps it is time we get to know the ‘beast’ and learn about its chameleon-like personality. Depending on the context where it has been analyzed, it bears different names and has been depicted slightly differently. But as you are about to learn, it seems to follow pretty much the same pattern—it is in fact, an archetype. Indeed, the process of change is nothing else than the evolutionary pattern of life and creativity—a pattern that pervades the entire Universe.

I begin the inquiry with the well-known story of the birth of the butterfly. Next, I use complexity and chaos theories to shine some light onto the evolutionary pattern of change. Finally, I borrow from other fields of inquiry such as chemistry, ecology, organization theory, story telling, mythology and the creative process to show the similarities in the way the process of change has been described from these different perspectives.

The Birth of a Butterfly

A real miracle, the birth of the butterfly is an irreversible transformation, in the chaos of the pupa. Evolution biologist Elisabeth Sahtouris tells the story:

“Inside a cocoon, deep in the caterpillar’s body, tiny things biologists call ‘imaginal disks’ begin to form. Not recognizing the newcomers, the caterpillar’s immune system snuffs them. But they keep coming faster and faster, then begin to link up with each other. Eventually the caterpillar’s immune system fails from the stress and the disks become imaginal cells that build the butterfly from the meltdown of the caterpillar’s body.

If we see ourselves as imaginal discs working to build the butterfly of a better world, we will also see how important it is to link with each other in the effort, to recognize how many different kinds of imaginal cells it will take to build a butterfly with all its capabilities and colors.”

The butterfly story has become a metaphor for social change, as our old systems are slowly collapsing to hopefully give rise to a vision of human society in which people live in harmony with others and with nature.

Complex Adaptive Systems Adaptation at the Edge of Chaos

Without going too deep into the theories, complexity science and the theory of complex adaptive systems teach us that complex adaptive systems (CAS) and living systems (LS) adapt to changes occurring in their environment in a state away from dynamic equilibrium, at the edge of chaos—a paradoxical transition phase of simultaneous stability and instability. At the edge of chaos, when the conditions are right, the components of CAS and LS are able to spontaneously self-organize, without any blueprint. The result is the emergence of new structures of higher-level order and new patterns of organization better adapted to the environment. This creative process, taking a system from dynamic equilibrium to the edge of chaos, and, then, to a higher state of order, coherence and wholeness is depicted on Figure 2. It is important to note that emergence is never a guarantee. When the system does not have the required learning capacity to creatively self-organize and transform, it may go through an immergence—a process of disintegration and complete breakdown.

The Evolutionary Path of Chaotic Systems

Obviously, a system may go through multiple phases of change throughout its life—alternating between periods of stability and instability, continuity and discontinuity, order and chaos. The pattern described in the previous section, when viewed from an evolutionary perspective, looks like Figure 3. The system progressively moves away from equilibrium until it takes a deep dive toward the “Chaos point” where the bifurcation resides: from there, the system may take a breakthrough path or a breakdown path (Laszlo, 2010). And the process repeats throughout the life cycle of the system.

Order Arising from Disorder in Dissipative Structures

Ilya Prigogine (1917-2003) won the 1977 Nobel Prize in chemistry for his work on dissipative structures, which demonstrates that order can arise from disorder. Prigogine showed that, left on its own, a mixture of specific substances in a dish results in a chemical reaction that creates concentric patterns spiraling for several hours at the surface of the dish (Fig. 4). The ordered patterns represent a decrease in entropy (i.e., increase in order) within the dish—entropy that is dissipated to the environment. Here again, when energy and matter flow between an open system and its environment, order and patterns emerge when the system is far from thermodynamic equilibrium, i.e., at the edge of chaos.

Fig. 4 - Belousov-Zhabotinsky Reaction (Source: http://www.ux.uis.no/~ruoff/BZ_Phenomenology.html)

Four Phases of the Adaptive Cycle of Natural Ecosystems

Researchers have discovered that natural ecosystems proceed through recurring cycles consisting of four phases: rapid growth, conservation, release, and reorganization (Walker and Salt, 2006). A description of the nature of these phases, including examples of how they can be interpreted in the realm of social organizations is as follow:

- The Exploitation Phase (r Phase) is a period of rapid growth. The components of a system are weakly interconnected and act independently without the need for much regulation. (e.g., a business start-up phase.)

- The transition from the r Phase to the Conservation Phase (K Phase) proceeds incrementally. Connections between agents in the system increase and resources (energy and materials) slowly accumulate. Specialization and economy of scale develop for greater efficiency. The system becomes more strongly regulated. Growth rate slows down and the system loses some flexibility. The system becomes more vulnerable to disturbance. (e.g., a medium to large business that perhaps grows from a local producer to a national and then global company.)

- The transition from the K Phase to the Release Phase (Omega Phase) may be sudden. The system’s resilience is not sufficient to absorb the trigger or disturbance and its structure breaks down. (e.g., an organization or industry facing a disruptive technology or a market shock.)

- The Reorganization Phase (Alpha Phase) is a chaotic phase of great uncertainty where all options are open. This phase where creativity, innovation, experimentation pay off leads to renewal of the system. Novel combinations of species can generate new possibilities that will be tested in the future. Of course, the possibility for system collapse is always present in this phase where success is never guaranteed. (e.g., innovations in an organization or the emergence of a new market.)

Fig. 5 – The Adaptive Cycle (Source: http://www.sustainablescale.org)

In Figure 6, I have superposed the four Adaptive Cycle Phases of ecosystems onto the Adaptive process of living systems at the edge of chaos graph to show the overlap of the different phases:

- The Conservation Phase K at the state of dynamic equilibrium.

- The Release Phase Ω, as the system’s structure starts to breakdown faced with disturbances (internal and external).

- The Reorganization Phase a, a chaotic phase of learning, creativity and self-organization.

- The Exploitation Phase r, when the system reaps the benefits of its transformation and grows, before its growth starts to slow down and the system enters a new K Phase.

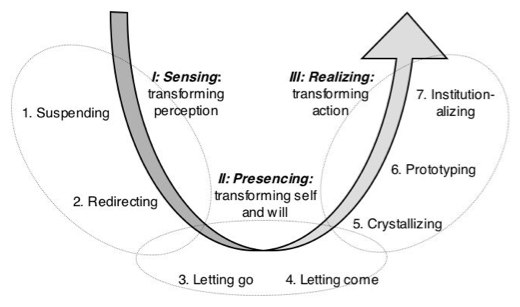

Theory U

Otto Scharmer’s seminal work on Theory U provides another perspective of the process of change, albeit applied to social systems. Theory U depicts a method or process to help individuals and groups move through different stages of cognition, while deepening the level of learning and insights from one stage to another. The different stages of cognition are: downloading; seeing; sensing; presencing; crystallizing; prototyping; performing and embodying (Scharmer, 2007).

Fig. 7 – The U Movement: Three Spaces, Seven Capacities (Source: Presencing Workbook, Senge, Scharmer, Jaworski, Flowers)

One should not fail to notice the similarity and overlap between the adaptive process of complex adaptive systems at the edge of chaos (Fig. 2) and the U Movement (Fig. 7). A social system in a stage of downloading operates at a dynamic equilibrium, maintaining its performance through the application of routines and best practices. Faced with the need to change, the system may start challenging its old assumptions and worldviews. As it does so, it begins to see reality with fresh eyes and uncovers deeper patterns that perhaps kept the system stuck. Slowly, the system is becoming aware of the fact that its own structure is, in fact, responsible for creating the behaviors that need to change. Entering next the stage of ‘not-knowing’ the system becomes more open to authentic learning, and potentially able to connecting to a deeper source of knowledge and insights. This stage is often uncomfortable, as the system must remain there long enough, at the edge of chaos, for self-organization and emergence to occur. This is a highly creative state, should one be patient enough to accept the confusion in which one might find oneself. In a state of Presencing, when insights arise, knowing what decisions to make and strategy to implement seem very straightforward: the path ahead is now obvious: the system starts prototyping and testing the new ideas and strategies and eventually, implementing them at a large scale. Eventually, the system achieves a higher state of knowing and level of consciousness—a new dynamic equilibrium.

The Three Act Story Structure

I find it quite interesting that the basic three act story structure used in plays or movies follows a similar pattern (Fig. 8a and Fig. 8b). In the Beginning act, the characters in their normal life situation are introduced (i.e., at their dynamic equilibrium). Slowly, the story develops, describing the situation and “conflict” the characters face, i.e., the disruption in their lives. In the Middle act, the story develops through a series of complications and obstacles (some resolved, others unresolved) finally leading to the ultimate tension and crisis—the Climax. In the final act, the End, the climax and the issues are rapidly resolved and the tension dissipates.

Fig. 8a and 8b – 3 Act Structure (Source: http://www.musik-therapie.at/PederHill/Structure&Plot.htm)

This story structure has been used through the ages all over the world in myths and tales to reflect the pattern of our personal and collective struggles: it represents the pattern of life and transformation and was captured eloquently by Joseph Campbell’s Hero’s Journey, which I’ll describe next.

The Hero’s Journey

The Hero’s Journey has three main phases, each including multiple steps. In the first phase—Departure—the hero is presented with a call for adventure, the initial indication that something is going to change. Often, the hero refuses the call because of all the familiar reasons of inertia, fear, sense of inadequacy and so on. When the hero finally commits, s/he may often receive the help of a supernatural protective figure. This is the point when the hero must cross the threshold, i.e., go through an ordeal to move from the every day world to the world of adventure. The hero enters the “belly of the whale” which represents the final separation between the old world/self and the potential for a new world/self.

The second phase—Initiation—is marked by a series of adventures that test the hero’s ability to move to the next stage of his/her development. Even though supernatural helpers will often support the hero through his journey, s/he might fail some of the tests. The meeting with the goddess is a critical phase when the hero experiences unconditional love and begins to see her/himself in a non-dualistic way. The hero will eventually have to face the monster, wizard, or warrior in the final battle (climax of the journey). This is the ultimate test when the transformation takes place: the ‘monster’ i.e., the ‘old self’ in the hero must be ‘killed’ so that the new self comes into being.

The final phase—Return—is not as easy as it might seem. It is often as dangerous to be returning from the journey, as it was to embark in it. The hero may need the help of guides, especially if the transformative experience has weakened him or her. So the hero must again cross the threshold of adventure and do so while preserving the wisdom gained on the quest. S/he must find ways to integrate all the learning into human life and share it with other—not a trivial thing to do. The hero must be master of two worlds, i.e., able to achieve a balance between the material and spiritual worlds. As a result the hero gains a new level of mastery: the freedom from the fear of death, which is the freedom to live.

In the Hero’s Journey, we once again witness the same pattern of becoming. As personal life crisis or challenges pushes us to leave the comfort of our everyday routine (stable state), one is faced with the choice of accepting or refusing the call of adventure. Accepting the call forces us to move to the edge and face our own demons. The more we are able to let go of the old ways of thinking and patterns of behavior—a process often felt as an internal “death”—the more we can learn and transform ourselves until we emerge from the abyss, through the process of rebirth, as a new Being, able to operate at a higher level of complexity and wholeness. The challenge is then to integrate the learning into our lives and ways of being so that we can act from a different place—a place of increased wisdom and love.

Fig. 9 – The Hero’s Journey (Source: http://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Monomyth)

The Creative Process

The transformative change process is a highly creative process very similar to the process that artists go through when they authentically create. As art psychologist Anton Ehrenzweig (1967) explains, the creative process is related to the primary process when the unconscious scans the chaotic oceanic state of undifferentiated order (i.e., a state where everything is connected and whole). In contrast to the conscious state, which per nature fragments and differentiates, the unconscious is able to access the great complexity of undifferentiated structures that are at the origin of dreams and unconscious phantasy. For the artist, the challenge is to tap into undifferentiated order without letting the ego take control over the process by creating defensive and rigid responses when stressed with the anxiety that inevitably is associated with the chaotic phase. When the ego is able to yield a shift of control, the unconscious becomes a source of insights, which the conscious mind can use, in the secondary process, through a process of dedifferentiation as the mind returns to a conscious state of awareness to exploit the insight and create something new.

The work of the artist Jackson Pollock is, for that matter, particularly interesting. Indeed, it has been demonstrated that what one might dismiss as “random” drips of painting, are actually an in-depth, intuitive study of “certain features of fluid dynamics” where the artist uses physics as its partner in this seemingly co-creative process — and he performed this before any physicists thought of studying fluid dynamics (see article: The Cutting_Edge Physics of Jackson Pollock, Wired Magazine, July 5, 2011).

The primary process, which I believe is identical to a state of Presencing (Senge, Scharmer, Jaworski, Flowers, 2004), is an embodied experience of pre-cognition and of sensing the whole; it requires breaking up the pattern of thought while awakening the creative unconscious mind. This process is source of direct and intuitive knowledge that often emerges in a flash of understanding. Any individual, whether in the arts, science, or in other creative domains (including management) must have the capacity to navigate this process in order to be creative.

Fig. 10 – Jackson Pollock at work (Source: http://www.apartmenttherapy.com/jackson-pollock-painter-physic-150631)

Conclusions

Through the review of diverse models, I aimed to demonstrate that whether in the domain of nature, social systems, or individual creativity, the process of transformative change follows the same evolutionary pattern. The process is very much fractals in that it operates in a similar fashion at the level of an individual, group, organization, but also at the level of society, nature/ecology and at the level of the whole universe. I believe that by gaining some familiarity with the pattern and its related phases one might be able to identify where we are in the process at any given time, make sense of the confusion when it arises and be better equipped to ride the wave of change. In addition, it is critical to learn which specific tools are best appropriate to facilitate each one of the phases so that to meet their requirements and achieve their respective purposes. Finally, one must develop the capacity to maintain ourselves, at the edge of chaos, using our unconscious as a means to access deeper insights. Accomplishing all the above requires commitment and practice. It also begins with engaging our heart in the process so that to not let us paralyzed by fear. Easier said than done!

Resources

Ehrenzweig, Anto (1964). The Hidden Order of Art: A Study in the Psychology of Artistic Imagination. University of California Press.

Jaworski, J., Kahane, A., Scharmer, C. O. PresenceWorkbook. Society of Organizational Leaning.

Laszlo, Ervin (2010). The Chaos Point: The World at the Crossroads. Piatkus.

Scharmer, Otto C. (2007). Theory U: Leading from the Future as It Emerges. Society of Organizational Leaning, Cambridge, Massachusetts.

Senge, P., Scharmer, O. C., Jaworksi, J., Flowers, B. S., (2004). Presence: Human Purpose and the Field of the Future. Society of Organizational Leaning, Cambridge, Massachusetts.

Walker, B. and Salt, D. (2006). Resilience Thinking: Sustaining Ecosystems and People in a Changing World. Island Press.

The Butterfly Story

- http://thelearninghost.com/butterflyconnection/imaginal-cells-part-one/

- http://www.sahtouris.com/ – 5_3,0,

The Three Act Story

- http://www.musik-therapie.at/PederHill/Structure&Plot.htm

- http://digitalworlds.wordpress.com/2008/04/07/story-arcs-and-the-three-act-structure/

The Hero’s Journey

- http://orias.berkeley.edu/hero/index.htm

- http://www.mcli.dist.maricopa.edu/smc/journey/ref/summary.html

Jackson Pollock’s Physics

Wild! The process i have stumbled towards is this very archetype – and I use it in innovation planning (Thoery U), innovation storytelling (hero’s journey), the cheeky disruptive innovation tool (creative process above) i have been working on, and above all the psycho-spiritual enlightenment tool I use for personal transformation (the butterfly of course). AWESOME to see some of the background and to connect with you. I am calling it The Switch